About the author

John Zeanah, AICP is the Chief of Development and Infrastructure for the City of Memphis, Tennessee. In this role, he leads a cross-functional team of agencies responsible for planning, housing, transportation, public works, and community and economic development. Prior to this role, John served as the Director of the Memphis and Shelby County Division of Planning and Development for over seven years. Among his accomplishments, John led the development and adoption of the Memphis 3.0 Comprehensive Plan, the City’s first comprehensive plan in 40 years and winner of the American Planning Association’s Daniel Burnham Award of Excellence for a Comprehensive Plan in 2020 and a Charter Award from the Congress for the New Urbanism in 2021. John is also Principal and Owner of Interval, LLC, a planning and policy advisory firm that specializes in helping public sector clients better understand, implement, and improve their plans, policies, codes, regulations, and processes.

Acknowledgements

A special thanks to Eric Kronberg, Rita Anderson, and Andre Jones for providing review, comments, and insight to help shape this article.

Introduction

In recent years, planners have made zoning reform a key priority to enable housing supply, including “missing middle” housing. In support of these efforts, the American Planning Association partnered with the National League of Cities to produce the Housing Supply Accelerator Playbook, a collection of strategies to advance housing supply across multiple dimensions, including regulatory reform. While much of the planning profession’s efforts toward this goal have focused on zoning reform, planners across the country are discovering that codes and regulations other than zoning can pose equally daunting barriers. Small multifamily projects – from triplexes and fourplexes up to mid-rise apartments – may win the zoning battle but lose the code war. Building codes, fire codes, stormwater rules, and utility requirements can all unintentionally penalize a small multifamily infill project as if it were a high-rise development. Even where zoning now allows middle-scale housing, these projects may remain hard to build because hidden regulatory hurdles drive up costs or complexity beyond what small developers can handle.

This article explores the barriers beyond zoning that can hold back development of middle-scale housing. It begins with a background on why these lesser-known codes matter for housing diversity. This is followed by a case study of a project in Memphis, highlighting the non-zoning barriers posed to the development of an infill collection of cottages and small apartment buildings, and how they were overcome. Next, the article delves into specific categories of barriers, from building codes and fire safety mandates to infrastructure and local ordinances, explaining how each can impede middle-scale housing projects. Finally, it concludes with an Action Steps for Planners section, offering implementable strategies for reforming codes and coordinating across departments to unlock middle-scale housing development.

Planners are becoming more interested in the role of building codes in enabling or preventing middle-scale housing, but often lack a building code background or the authority to effect change in their cities and towns. This article is intended for planners with a limited background in building codes who are looking for a practical, policy-oriented overview of how building codes and other regulations beyond zoning affect housing supply and affordability. The goal is to equip planning professionals to recognize these obstacles and work proactively on solutions. By looking beyond zoning to the finer-grained codes and regulations, communities can truly welcome the gentle density of small multifamily that so many zoning reforms aim to permit.

1. Background: Why Barriers Beyond Zoning Matter for Middle-Scale Housing

Many communities have made great strides in reforming exclusionary zoning. Single-family-only zones are being opened up to duplexes, triplexes, and other types of housing, from Minneapolis and Portland, Oregon, to recent statewide initiatives in California, Washington, Montana, and Maine. These zoning changes are intended to spur the development of “missing middle” housing, typically defined as small multifamily structures between single-family homes and large apartment buildings. This middle-scale housing can help communities gently increase density, improve affordability, and expand housing choice in walkable neighborhoods.

However, communities are also finding that simply allowing a fourplex on paper does not guarantee that one will be built. Planners are beginning to realize that even where zoning allows small multifamily housing, other codes often make it infeasible to build. Building construction codes, fire safety mandates, stormwater regulations, and utility standards were written mainly with either single-family homes or much larger buildings in mind, not the middle-scale projects in between. As a result, a triplex, an eight-unit cottage court, or even a 24-unit mid-rise apartment can unintentionally trigger “big building” requirements, which add significant cost or complexity and negate the modest scale advantage of these projects.

This artificial divide often starts when a project crosses the threshold between two and three units. National model codes classify any building with three or more dwelling units as an apartment building, subject to the full commercial building code, the International Building Code (IBC). In many instances, other codes and regulations follow suit. In contrast, most one- and two-family homes fall under the simpler International Residential Code (IRC) and often simpler stormwater or utility requirements as well. A fourplex may be treated like a 40-unit apartment in many respects, requiring features such as fire sprinklers, commercial-grade alarm systems, accessibility measures, heightened design load requirements, and often more stringent stormwater management improvements. These requirements, particularly life safety provisions, may be justified for larger buildings and sites, but for a small multifamily project, they can be burdensome relative to the risks. The outcome is that many missing middle projects do not pencil out or become technically challenging, even if allowed by zoning. A study in California prepared for the San Francisco Planning Department, for instance, found that five- to 10-unit infill buildings are often not financially feasible without subsidies, partly due to per-unit cost increases from code requirements.1

In short, codes beyond zoning can inadvertently undermine the very housing types that zoning reform is trying to enable. This is especially true for middle-scale housing: small enough that developers cannot achieve big economies of scale, yet large enough to fall into more stringent regulatory regimes. These projects are typically undertaken by local, often first-time or small-scale developers rather than large professional firms, who may struggle to navigate complex code compliance and hefty upfront infrastructure costs. The risk is that zoning reforms yield far less housing on the ground than expected, due to the range of additional code requirements that are not typically on planners’ radars.

Fortunately, awareness of these hidden barriers is growing. Innovative jurisdictions have begun to adjust building codes and standards to better calibrate requirements for small multifamily buildings. States like Tennessee and North Carolina recently changed laws to ease code hurdles for three- to four-unit structures. City agencies are working with utilities to modify archaic policies – for example, redefining when a building is considered “commercial.” In my own experience, working with the Malone Park Commons project in Memphis, Tennessee, provided me with a case study in overcoming these obstacles, which also prompted local code amendments and even state legislation. By understanding why a fourplex could trigger commercial fire codes or a cottage court could trigger extra utility fees, planners can better advocate for sensible and proportional codes that scale with the size of the development, allowing middle-scale housing a better chance to get built. The following sections explore the most common categories of these barriers beyond zoning, with examples and lessons for reform.

2. Case Study: Malone Park Commons – Building Small Multifamily, One Obstacle at a Time

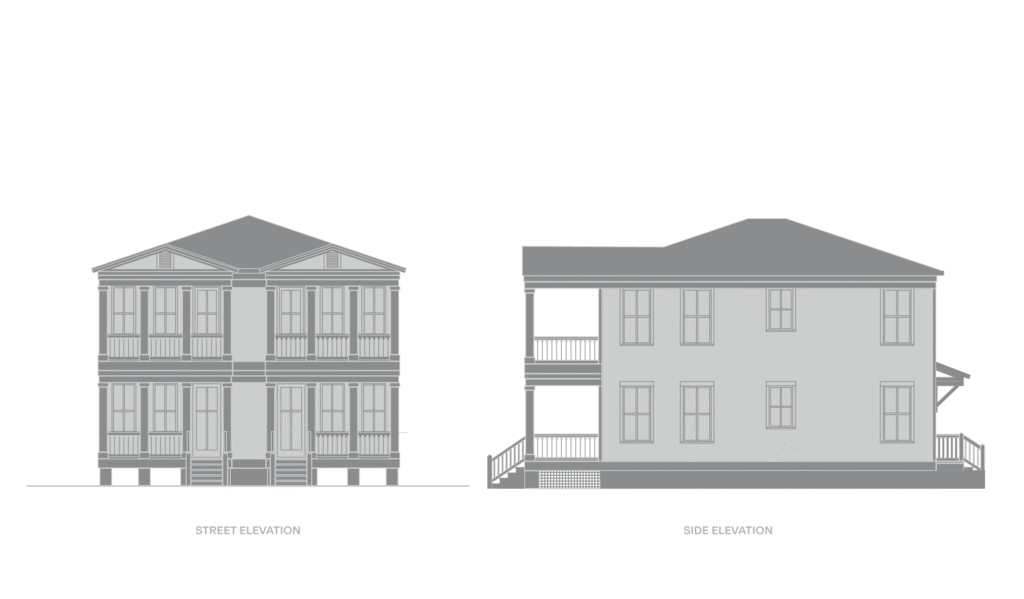

Malone Park Commons, located in Memphis, Tennessee, is a 35-unit cottage court-style development that has become a proving ground for the kinds of hurdles beyond zoning code that small-scale multifamily housing faces. Designed as a model for missing middle housing in walkable neighborhoods, the project aimed to deliver compact, modestly priced units in an infill context – but found itself repeatedly blocked by legacy building, fire, utility, and tax regulations written for much larger-scale development.

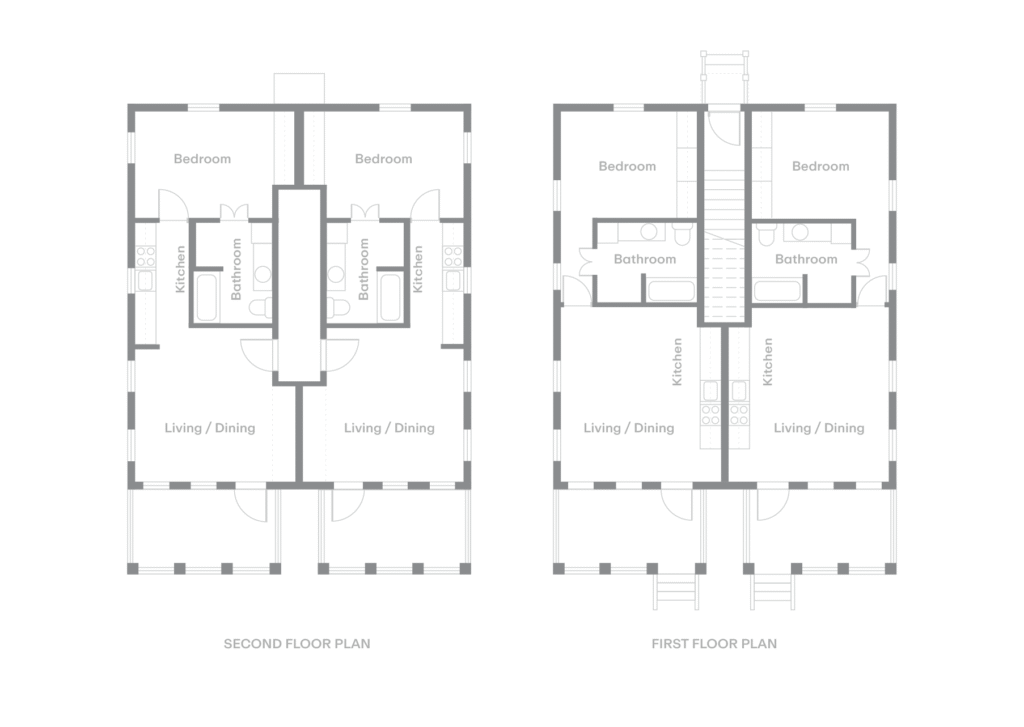

The first phase of Malone Park Commons consisted of eleven detached cottages arranged around a shared green space. Later phases introduced two live-work fourplex buildings and four purely residential fourplexes, transitioning seamlessly to conventional detached single-family homes. This demonstrates that it is possible to build “gentle density” with thoughtful urban design. But the path to getting those units approved, permitted, and built exposed a web of regulatory obstacles that ultimately led to state legislation and local code reform.

2.1 From House-Sized Buildings to Commercial-Scale Requirements

The design of Malone Park Commons focused on human-scale housing types: small detached or semi-attached structures no taller than two stories, with private front doors, porches, and pedestrian courtyards. But as soon as the unit count for any given building exceeded two, the development was brought under the commercial building code regime of the International Building Code (IBC) and more stringent local regulations. That meant:

- Full NFPA 13 or 13R sprinkler systems, requiring costly water infrastructure

- Backflow preventers for each fourplex, triggering equipment, and maintenance costs2

- Professional stamped plans and structural designs that would not have been needed under the International Residential Code (IRC)

- Fire alarm panels and pull stations

In practice, a fourplex built at Malone Park Commons was held to the same building code standard as a 35-unit apartment building, despite having a much lower height, occupancy load, and risk profile.

One of the most frustrating surprises for the developer came from utility classifications. Because the fourplex buildings were technically “apartments,” the local water utility treated each one as a commercial account. That meant:

- Requiring a backflow preventer for each building, at a cost of roughly $3,000-$5,000 per installation

- Applying commercial water tap fees, even though the buildings functioned more like townhomes

- Assessing base service fees and meter costs that were much higher than for a single-family home

- According to project developer Andre Jones, these water infrastructure costs were unexpected, unscalable, and financially destabilizing – significant obstacles to completing later phases. The developers argued that form and scale, not just the number of units, should determine how utilities classify a building.

2.2 Sprinklers vs. Fire-Rated Separations: A Push for Alternative Fire Safety Compliance

One of the most consequential debates centered on the requirement for fire sprinklers in small multifamily buildings. Malone Park’s developers argued that their live-work and purely residential fourplex buildings, capped at two stories and designed with ample separation, could achieve equivalent or better fire safety by using two-hour-rated separations between units and installing smoke alarms.

Initially, this would have been allowed under a local amendment made to the Memphis and Shelby County building codes, but this quickly ran into issues with the state fire marshal’s interpretation of the code. Persistent advocacy from a network of local partners led to a policy breakthrough: in 2024, the Tennessee legislature passed HB 2787, which explicitly permits residential buildings of up to four units and under 5,000 square feet and three stories to be built without a sprinkler system if two-hour-rated assemblies are provided instead.3 This legalized the trade-off that the local code amendment had set initially and has now paved the way for other small infill projects across the state to avoid unnecessary costs while maintaining life safety standards.

2.3 Lessons from the Ground

Malone Park Commons illustrates just how deep the regulatory barriers to small multifamily development go. Even a well-zoned site with community support and good design can be undone by fire protection rules, utility service classifications, and misaligned building codes. The developers did not just encounter these problems – they documented and explained them, using their experience to build support for reform. For local planners, Malone Park Commons became both a cause and a learning environment, leading to not only real change but also a collaborative partnership between planners and developers to better understand the breadth of code hurdles holding back missing middle housing and what to do about them.

The partnership between planners and the Malone Park Commons developers directly led to state legislation that provides relief from costly sprinkler requirements, modified utility rules for backflow prevention, and administrative flexibility for locating ground floor retail and services in smaller mixed use buildings.

Today, Malone Park is more than a housing development – it’s a proof point for how to modernize code for missing middle housing. It shows that with the right policies in place, cities can allow incremental, human-scale housing to be built without compromising safety or quality. It shows how planners, code officials, developers, utility providers, and lawmakers can work together to update the rules that no longer fit the housing we want to build.

3. Building Code Hurdles: When Housing Meets the Commercial Code

One of the first barriers a small multifamily project encounters is the building code itself. In most jurisdictions, the moment you propose a building with three or more dwellings under one roof, you leave the realm of the residential code (IRC) and enter the International Building Code (IBC), sometimes called the commercial code. The IBC is a comprehensive code designed for everything from apartments and offices to airports and stadiums. As Aaron Lubeck, a North Carolina-based developer, puts it, “The exact same codebook in America governs a triplex and an airport.”4 Despite some hyperbole on his part (different occupancy sections exist in the IBC), Lubeck captures the fundamental mismatch: the IBC’s provisions are often over-scaled for a house-sized building with a handful of units.

3.1 IBC vs. IRC: The “Apartment” Threshold

Under the IBC, a small multifamily building is typically classified as a Group R-2 occupancy (apartments).5 This classification triggers a host of requirements that do not apply to one- or two-family dwellings under the IRC. For example, the model IBC mandates that R-2 buildings be equipped with automatic sprinkler systems6 and, for buildings above three stories, have two separate exits for occupants placed at a distance from each other, among other provisions.7 By contrast, the IRC treats a duplex almost like a single-family home, with no sprinkler mandate in most states and simpler egress – often just doors and windows for each unit.8 The leap in complexity from duplex to triplex is dramatic.

Key differences that apply once you cross the threshold between two and three units include:

- Professional Design Requirements: A small apartment building typically must be designed and stamped by a licensed architect or engineer to meet IBC structural and life-safety standards, as well as state licensure rules that often kick in at a similar threshold. A single-family or duplex can often be built to simpler prescriptive standards without full structural design requirements, including engineered calculations for wind, seismic, and lateral loads.9 Separate state laws may also introduce requirements – for example, Tennessee requires a registered design professional to prepare plans and specifications for residential occupancies with more than two stories or 5,000 square feet of gross floor area.10 This means higher soft costs for design and higher hard costs for certain structural elements in a small multifamily building that may be the same size as a large single-family home. Jurisdictions should explore allowing small multifamily to use IRC prescriptive structural provisions for elements like wind, snow, and seismic to avoid requiring costly engineering, as long as the building is modest in height and wood-framed.

- Fire-Rated Separation and Construction Type: The IBC may require higher fire-resistance-rated construction between units, such as one-hour or two-hour fire-rated wall separations and floors, and limits on wood frame construction for multifamily buildings.11 The IRC also requires fire separation (e.g. one-hour separations for duplex common walls), but IBC standards can be more extensive. These assemblies can increase material and labor costs. We’ll discuss later how some codes allow either sprinklers or thicker fire separations as compliance alternatives for small projects.

- Height and Area Limits: While small missing middle buildings are naturally limited in size, the IBC places restrictions on maximum building height based on occupancy type, construction type, and sprinkler system present.12 The IRC has height limits too (three stories for a townhouse, for example), but is tailored to house-sized structures.13

- Energy Code Differences: In some cases, multifamily buildings are subject to commercial energy codes, which can result in different insulation, HVAC, and testing requirements compared to the residential energy code for single-family homes (IECC). This can be another subtle cost increase for the same physical structure.

In summary, the code divide between IRC and IBC acts as a hard line beyond two units (or one unit if the dwelling is attached). Planners have begun to realize that if we want a house-scale multi-unit building to be built as inexpensively as a large house, we may need to adjust where that line is drawn. In 2021, Memphis and Shelby County, Tennessee, amended their building code to allow up to six-unit buildings to be reviewed under a local amendment to the International Residential Code (IRC), also known as the “Large Home Amendment.” This local change recognized that a six-unit, two-story building can be safely built to a modified residential code, rather than treating it like a large apartment complex. However, the Tennessee State Fire Marshal’s office disagreed. To resolve the dispute, Memphis pursued state legislation on sprinkler reform instead, but kept conversations open with the State Fire Marshal on potential future amendments.

Similarly, in 2023, North Carolina passed legislation (HB 488) requiring that triplexes and fourplexes be governed by the residential code, rather than the commercial code. In 2025, the City of Dallas updated their codes to permit up to eight units in the residential code. By making similar changes, jurisdictions can eliminate many of the costly requirements that were previously automatic for smaller multifamily projects – a reform expected to significantly lower construction costs for missing middle housing. These pioneering reforms at the state and local level illustrate a key principle: calibrate building code standards to building scale. A small plex house should not need to meet the same code checklist as a larger apartment building.

3.2 Sprinkler Mandates and Fire Safety Trade-Offs

Perhaps the most notorious building code hurdle for small multifamily housing is the automatic sprinkler requirement. Sprinkler systems are effective tools for reducing property loss in the event of a fire. They are also effective systems for life safety, though other, equally effective methods exist. But sprinkler systems also add considerable cost and require ongoing maintenance, as well as sufficient water pressure and infrastructure. Under the IBC, generally applicable to buildings with three or more units, any new R-2 multifamily building must have an automatic fire sprinkler system in accordance with NFPA standards.14 By contrast, the sprinkler requirements for one- and two-family dwellings have been removed from state adoptions of the IRC in 46 states, and two other states have limited requirements based on the size of the home.15

For small projects, sprinklers can be a make-or-break factor. It’s not just the cost of the pipes and sprinkler heads – the need for a water supply line, often a dedicated larger-diameter service, backflow preventer, and possibly a water meter upgrade or pump, can escalate costs. In neighborhoods with low water pressure, a small infill development might even need the city to upgrade the water main or install costly fire pumps or tanks. Sprinkler installation alone can cost tens of thousands of dollars for a fourplex, and a commercial-grade backflow prevention device for the system can cost several thousand more to install on a small building.

One of the main reasons behind Memphis’s Large Home building code amendment was to allow three-family and four-family buildings under 5,000 square feet to trade two-hour-rated separations between units in place of sprinklers. When this local amendment was met with disapproval from the Tennessee State Fire Marshal’s Office, the planning office partnered with local homebuilders and housing advocates to write state legislation to codify this exception. In 2024, the Tennessee General Assembly passed HB 2787/SB 2635 specifically to enable such flexibility. This law not only allowed Memphis to keep the most critical piece of its local Large Home Amendment but also helped other jurisdictions in Tennessee see that increased fire-rated separations plus smoke alarms in a small building can protect residents while reducing costs, thereby enabling more missing middle housing.

It’s important to emphasize that the value of sprinklers is not in question, but rather a question of cost, proportionality, and practicality. For small multifamily structures that require a complete NFPA-compliant sprinkler system, along with associated water infrastructure, the cost per unit is considerable. The broader trend is recognizing that a one-size-fits-all fire safety approach can price small projects out; thus, offering alternative compliance or scaled requirements is key. We will also revisit sprinklers in the fire code section, since the type of system (NFPA 13, 13R, or 13D) matters for small buildings.

It should be emphasized here, however, that increasing fire separation does increase construction costs. A builder not only needs to factor in the cost to increase the thickness of separation walls and ceilings but also cost increases for structural reinforcement to support thicker separations. When considering thicker separation to offset sprinkler requirements, make sure alternative compliance options do not overcorrect and increase the cost burden. Too much additional structural load can not only wipe out any savings from removing sprinklers, but it can also wipe out savings from moving a small multifamily building from the IBC to the IRC, too.

3.3 Egress and Exiting Challenges

Another significant building code hurdle is designing adequate means of egress (exits) for a small multifamily structure. The IBC requires that occupants have at least two ways to exit a building in an emergency, which typically means two separate stairs or exit paths, when certain occupant loads or building configurations are exceeded. Multifamily buildings above three stories in height require two exits, generally leading to two enclosed stairwells on opposite ends of a central common corridor. 16 Small buildings can get caught by these rules in ways that complicate their design and footprint.

Providing two staircases in a small building consumes a lot of floor space and construction costs, which may make the units smaller or fewer in number. In many traditional “missing middle” building types, like a small walk-up apartment, there was often only a single staircase, sometimes with exterior fire escapes. Building codes in most of the United States, unlike most of those abroad, have historically required a second stair above a low-rise height, and the latest generation of codes have made the standards that the second exit must be built to stricter. Some cities and states, however, are rethinking this for small-footprint mid-rise buildings.

Seattle is notable for having long allowed single-stair apartment buildings up to six stories at four units per floor. The benefits of single-stair buildings are that they can be designed safely, including with automatic sprinkler systems, and allow for much more efficient and livable layouts. They also consume less land area, enabling infill construction, and can be delivered at a lower cost per unit.

Several cities and states have followed Seattle’s lead. In 2023, Washington State passed SB 5491, directing the state building code council to develop code changes to allow single-stair multifamily buildings in the state’s building code, applying to jurisdictions outside of Seattle. Seattle’s building official submitted a proposal to the state’s code to allow such buildings under similar but slightly stricter conditions than Seattle itself allows, in an optional appendix to be adopted at the discretion of local jurisdictions.17 A bill was passed in Tennessee in 2024, allowing local governments to adopt a set of defined requirements to permit up to six stories with four units per floor served by a single staircase was similarly passed in Tennessee in 2024. As of this writing, Memphis, Knoxville, and Jackson, Tennessee, have adopted the new provisions.18

In 2025, a study by the Pew Charitable Trusts found that single-stair buildings, such as those permitted in Seattle and Tennessee, were just as safe as their dual-staircase counterparts.19 The study analyzed fire death rates in four- to six-story single-stair buildings constructed since 2012 in New York City and Seattle. It found that the fire fatality rate in these buildings was equivalent to that in other residential structures, with no deaths attributed to the lack of a second stairway. The report attributes this safety record to modern fire safety features, including fire-rated separations, self-closing doors, smoke detectors, and fire sprinklers. Additionally, research from the Netherlands, where single-stairway buildings are common, supports these findings, showing comparable fire safety outcomes. The report concludes that, when built with contemporary safety measures and design limitations, single-stairway buildings can safely contribute to increasing housing supply.

The takeaway for planners is that egress rules can be relaxed for small-scale buildings without sacrificing safety, and doing so can meaningfully reduce construction complexity. Until such reforms are widespread, however, many missing middle designs are forced into awkward shapes or lower heights and unit counts to accommodate the requirement for two means of egress for buildings above a low-rise height.

In summary, exiting requirements meant for larger buildings can constrain the form of a middle-scale housing project. Planners should be aware that an extra staircase and exit corridor can consume 7 percent of a small-footprint building’s floor area and can account for 10 percent its total construction cost, which in turn drives up per-unit costs or reduces unit size.20 By advocating for code flexibility, such as single-stair allowances with appropriate safety compensations, planners can help unlock more creative and efficient small-scale designs.

3.4 Accessibility Requirements for Small Multifamily

Accessibility is another critical factor that often becomes a concern once a building reaches a certain number of units. The Federal Fair Housing Act (FHA) requires that in any new multi-unit residential building with four or more units, a certain baseline of accessible or “adaptable” design features be provided in the units and common areas. This includes features like accessible entrances, wider doors and hallways, reachable light switches, and bathrooms that can be adapted for use by someone in a wheelchair, though not fully outfitted as a “Type A” accessible unit. In a building without an elevator, these requirements apply to all ground-floor units; if there is an elevator, they apply to all units in the building.21

For a developer accustomed to building single-family homes, these accessibility mandates can be a new world. A fourplex must be planned with no steps at ground floor entrances, a wheelchair-friendly path through the unit, and reinforced bathroom walls for future grab bars, among other details. These may not be cost-prohibitive changes, but they do require thoughtful design and sometimes more significant site work considerations. For instance, placing a fourplex on a narrow infill lot may require grading or a ramp to ensure that at least one unit has an accessible entry if the lot slopes. Small-scale builders may also need to hire design professionals to ensure compliance, which adds to soft costs.

In our context of market-rate missing middle housing, the main point is that the fourth unit triggers federal accessibility design requirements. Duplexes and triplexes are exempt from FHA rules, so a lot of small developers never encounter this until they propose a quadplex. It’s a worthwhile requirement to provide inclusive housing, but it is another regulatory learning curve and cost factor at the small scale. Some developers might respond by limiting projects to three units to avoid the perceived complexity. Others proceed, but they must incorporate features that slightly increase construction costs and possibly reduce rentable square footage.

From a planner’s perspective, ensuring that missing middle housing is accessible to people with disabilities is an important equity goal – new housing options should serve all community members. Thus, finding ways to meet accessibility requirements without derailing projects is key. One strategy is to provide technical assistance or template plans that already comply with federal guidelines, so small builders do not have to start from scratch.

3.5 Extending Code Reform to Existing Buildings

Many of the barriers that prevent small-scale multifamily development under the International Building Code (IBC) also show up in the reuse and conversion of existing buildings, a process which is governed by the International Existing Building Code (IEBC). If jurisdictions only update the IBC, they risk limiting reform to new construction while continuing to burden or even block adaptive reuse projects that could otherwise deliver gentle density through incremental infill.

Planners should work with building officials to ensure that code flexibility extends to change-of-use and renovation projects. Converting a single-family home, small commercial building, or duplex into a triplex or fourplex often triggers a change in occupancy classification to R-2, which under the IEBC can require significant upgrades, including full sprinkler systems, egress stair duplication, accessibility retrofits, and structural reinforcement, even when the underlying building footprint and form remain modest.22

Model IEBC amendments can close this gap. For instance, jurisdictions can explicitly allow small multifamily reuse projects to comply with the same fire protection trade-offs allowed for new construction. Planners can also support allowing IRC-based structural provisions for wood-frame buildings under a certain height and limiting required accessibility upgrades.

Emerging best practices also suggest incorporating modern single-stair egress provisions into the IEBC, such as those adopted in Tennessee, for buildings up to six stories when sprinklers and travel distance limits are met. These reforms recognize that life safety can be maintained through performance-based standards without imposing commercial-scale interventions on inherently low-risk, human-scaled buildings.

The key is consistency: if a new fourplex can be built under simplified code pathways, then converting an old house into one should not require a more complex and expensive compliance route. Aligning IEBC amendments with new construction reforms sends a clear message that jurisdictions value adaptive reuse and understand the critical role of small, existing buildings in addressing housing needs.

3.6 Flexibility for Micro Mixed Use

Small multifamily buildings in walkable areas can be ideal locations for corner stores, live-work studios, offices, or small-scale service uses – uses that contribute to neighborhood vitality. Yet in many jurisdictions, building and fire codes treat any ground-floor commercial space as a higher-intensity use that triggers commercial-scale upgrades. For example, when Malone Park Commons wanted to lease ground floor space in their live-work buildings to commercial tenants, they learned the code required that they upgrade the sprinkler system from 13R to a full NFPA 13 system. For small buildings, these requirements often make mixed-use development infeasible, especially when the commercial space is no more than 500 to 800 square feet.

To enable these neighborhood-serving uses while preserving life safety, jurisdictions can amend their building and fire codes to allow limited Group B (business) occupancies within small multifamily buildings, with conditions that reflect actual risk. Group B occupancies cover a wide range of low hazard uses, such as offices, studios, professional services, and small retail, and can often be accommodated without expensive mechanical or suppression systems.23

A model amendment might allow a small multifamily building to include a ground-floor Group B occupancy regardless of whether the building is sprinklered provided there are no hazardous materials or cooking operations that would require specialized fire suppression or ventilation, the space has direct access to the exterior, and occupant load is limited to under 50 people. Alternatively, where sprinklers are not required in buildings with one or two dwelling units, the code could be interpreted to apply this to micro mixed use buildings with commercial occupancies as well.

This approach allows commercial uses that are compatible with residential neighbors to operate without overburdening the building with commercial code compliance. It also supports local economic development by enabling flexible live-work and service spaces in walkable neighborhoods, particularly in places where zoning has already been updated to allow mixed use, but where building and fire codes still pose barriers.

Importantly, jurisdictions should coordinate these allowances across departments, including building safety, fire prevention, and planning, to ensure small mixed-use projects are evaluated holistically and not penalized for their modest scale. When designed with guardrails around fire separation and occupant load, these uses pose no more risk than a large home office and can enhance the livability and economic diversity of neighborhoods.

In sum, building code and related federal requirements impose increased requirements once you surpass a certain unit count or size. Because these increased requirements are not proportionate to the scale, these steps can result in significant cost increases that impact a project’s pro forma. Sprinklers, second stairs, accessible design, along with design load requirements and energy code standards, are some of the biggest hurdles that tend to catch middle-scale projects by surprise. The good news is that many jurisdictions are pioneering solutions – from alternative compliance paths to statewide code changes – to right-size these building code requirements for small multifamily buildings. By doing so, cities and states aim to maintain life safety and inclusivity while removing unnecessary cost premiums for missing middle housing. Next, we turn to another set of hurdles: fire codes and the associated systems that often accompany building code issues.

4. Fire Protection Requirements: Big Safety Systems in Small Buildings

Building and fire codes are closely intertwined and provisions are often duplicated, but it’s worth examining specific fire safety system requirements that often present barriers for small multifamily projects. Beyond the structural elements discussed above, developers of a house-scale apartment building must also navigate fire alarm systems, various types of sprinkler systems, and other code provisions, typically geared toward larger occupancies. These requirements can involve introducing new equipment, requiring technical expertise, ongoing maintenance, and coordination with fire authorities.

4.1 Commercial Fire Alarm Systems and Detection

In a single-family home or duplex, fire protection is usually fairly simple: install residential smoke alarms in each unit (and perhaps carbon monoxide detectors) and you’re done. Small buildings usually are not required to have a centralized fire alarm panel or manual pull stations. However, for multifamily buildings, building and fire codes often mandate a building-wide fire alarm system once a certain threshold is exceeded. Required active systems associated with alarms can include an alarm control panel, hard-wired smoke detectors in common areas, manual pull stations near exits, and audible and visual notification appliances, including horns and strobes throughout the building. The International Fire Code (IFC) and the IBC require such systems for many R-2 buildings, especially if they are three stories or taller, have more than a certain number of units, or if the units do not have their own exits.24

For example, a common requirement for small multifamily is the installation of a manual fire alarm system with pull stations and audible and visual alarms unless each unit has its own exterior exit. Even without that exact trigger, local code officials might require an alarm panel if the building is sprinklered or if they feel it is needed for occupant notification. The cost of installing a commercial fire alarm system – including panel, wiring, detectors, strobes, and professional monitoring setup – can be several thousand dollars, plus monthly monitoring and telecommunications fees. More importantly for small developers, it is an additional contractor or trade (fire alarm specialist) and a coordination task that would not exist in a duplex project. It requires electrical drawings, possibly a separate permit, and annual inspections.

Malone Park Commons’ developers ran into this issue in their fourplex buildings. Because their live-work fourplexes were considered apartments, the code required features like pull stations and alarm horns. An alternative would be an amendment to the fire code that requires buildings with more than eight units or more than two stories to install a building-wide fire alarm system with manual pull stations, allowing smaller multifamily buildings to use individual smoke alarms in each unit. This kind of nuanced rule is an example of calibrating requirements based on a proportional scale – a fourplex that is closer in size to a large single-family home or duplex can rely on each unit’s smoke alarms to alert residents, similar to a house, rather than having a costly centralized alarm system.

Another aspect is fire department notification: larger buildings often require a direct connection so that if an alarm or sprinkler system goes off, it alerts the fire department or a monitoring company.25 For a small building owner, setting up and maintaining that monitoring service and the associated telecommunications line (and, sometimes, redundant lines) is a new ongoing cost.

In practical terms, planners should be aware that a small infill developer may face an unexpected requirement to include a fire alarm system with pull stations, or, conversely, may avoid it if local codes have higher thresholds. Technology is also helping; today’s interconnected smoke detectors, with 10-year batteries or wired connections, can cover an entire small building without a traditional panel, and some jurisdictions accept this as meeting the intent for occupant notification. The goal is to ensure early warning in a fire, without over-specifying an institutional-grade system for a small multifamily building.

4.2 Sprinkler System Types: NFPA 13 vs. 13R vs. 13D

Earlier, we discussed when sprinklers should be required. Where they are, the type of sprinkler system matters a great deal in terms of cost and complexity. National standards offer different sprinkler system designs for different building types:

- NFPA 13 systems are the most comprehensive and are required in most commercial and multifamily buildings. They cover all areas of a building (including attics, closets, and small spaces), and are designed to control a fully developed fire, with an ample water supply and often a fire department connection and alarms. One easy way to visually identify a NFPA 13 (or 13R) system is to look for “hard pipe,” often black steel pipe, running between sprinkler heads. The sprinkler riser, the point where the water line comes into the building with handles and gauges, is very robust.

- NFPA 13R systems are a scaled-down version of the standard for residential occupancies up to four stories high, commonly found in apartments and condominiums. They are life-safety systems designed mainly to allow occupants to escape. For example, they do not need to cover certain concealed spaces such as attics and have slightly lower water demand than 13 systems. 13R is cheaper than 13 but still requires a reliable water supply and is usually connected to an alarm.

- NFPA 13D systems are designed for one- and two-family dwellings, as well as single-family townhouses. They are the simplest: designed to protect lives in smaller residential structures. They can often run off the domestic water line, have a 10-minute water supply requirement, and cover fewer areas. NFPA 13D systems allow PEX or “plastic” pipe running between sprinkler heads. They typically do not require backup power or a fire department hookup.

For small multifamily, the code question is: which standard applies? Under the IBC, an R-2 building would normally use NFPA 13 or 13R, but not 13D, because 13D has been historically limited to one- and two-family applications. However, since most jurisdictions do not require sprinkler systems in one- and two-family dwellings, 13D is not used as often as a 13 or 13R system. However, allowing the use of NFPA 13D or modified 13R for middle-scale housing would help to reduce cost and provide adequate protection proportionate to building size. Tennessee’s new law allows localities to use the NFPA 13D standard for triplexes and fourplexes if they choose to mandate sprinklers. This standard could be helpful for small multifamily buildings with up to eight units or that are no more than two stories high. This is significant because a 13D system can often be fed from a regular residential water meter with a small diameter pipe, whereas a 13R or 13 usually requires a larger dedicated water service and a backflow device. The cost difference can be thousands of dollars, and it also affects whether you need a separate tap to the water main.

For example, consider a fourplex in most contexts: under the model codes’ interpretation, it’s R-2, so it needs a 13R system. The developer would then have to pay the city to install a two-inch sprinkler water line with a backflow preventer, possibly a separate meter for that line, and hire a sprinkler contractor to install a multi-zone system covering all rooms. If allowed to use 13D, the builder might simply upsize the domestic water line slightly and run a combined system (multipurpose piping that feeds sprinklers and fixtures) or a simple loop that covers the few required rooms. No separate fire department connection or direct monitoring is typically required for 13D. In a small building, that could cut the sprinkler system cost by more than half.

Some jurisdictions simply exempt small multifamily from sprinklers entirely, but others may find a middle ground of requiring sprinklers but at the 13D level. This could be an acceptable compromise if planners encounter resistance to removing sprinkler requirements from the building official or fire code official. Sprinklers could still be required to enhance safety, but at a scale appropriate for a small multifamily building, avoiding complex equipment, pumps, and risers, as well as their associated maintenance and monitoring.

As planners, knowing the difference between these NFPA standards can allow you to participate in these nuanced policy discussions with code officials in your jurisdiction. Code officials may initially balk at using a less costly system in smaller buildings, but NFPA research has found sprinkler systems to be very effective in preventing fatalities in residential fires without differentiation by type.26 For instance, NFPA reports demonstrate that the vast majority of fatal fires in residences start in living rooms, bedrooms,or kitchens – areas covered by 13D systems.27 Also, smaller buildings have fewer people and shorter egress travel distances, reducing risk factors.

Beyond sprinklers and alarms, building and fire codes may also impose requirements like fire department access, which can be troublesome on small sites – for example, needing a clear path or driveway for fire trucks within a certain distance of buildings. In tight urban lots, meeting those fire lane or turnaround rules may be impossible, so some leniency or creative solutions, like sprinklering as a trade-off for lack of full access, may be needed. Ensuring the fire department can reach all units might sometimes require installing standpipe connections or modifying site access to accommodate fire apparatus. Generally, if a building is under 30 feet tall and close to the street, fire apparatus access roads (otherwise known as fire lanes) are less of an issue. But many middle-scale housing projects exceed 30 feet in height, so it’s important to know how your codes treat these situations.28

To wrap up fire protection code hurdles, the main themes are the scale and complexity of systems. Small multifamily buildings can be very safe with simpler, lower-cost fire protection solutions, such as interconnected smoke alarms and possibly residential sprinklers, without needing the full suite of commercial fire infrastructure. Both local and state policy innovations are pointing in this direction, aligning fire safety requirements with the true needs of these buildings. Planners should involve fire officials in discussions early when crafting missing middle ordinances. Often, fire marshals are focused on safety outcomes and can be open to alternative methods as long as life safety is maintained. For example, a single-stair building might be acceptable to them if it’s fully sprinklered, has a small floor plate, is constructed of more fire-resistant materials, or has a smoke control system in the stairway, ensuring that one stair remains tenable in a fire. By finding these compromises, planners can help avoid scenarios where the building and/or fire codes price out or even effectively ban the very housing types communities want to see.

5. Stormwater Regulations: Managing Water on Small Infill Sites

Stormwater management is less obvious but can be a significant barrier to developing small-scale multifamily housing, especially in urban infill scenarios. Many stormwater regulations were written with larger subdivisions or commercial projects in mind, and they often impose fixed infrastructure requirements that do not scale down easily. A four-unit infill project might be expected to handle stormwater almost like a 40-unit project would, which can be disproportionately expensive or physically unworkable on a small site

5.1 On-Site Detention and Drainage Requirements

A common requirement in local stormwater ordinances is that new development must detain or retain stormwater runoff on-site so that post-development runoff rates do not exceed pre-development rates. In practice, this means adding features like detention ponds, underground storage tanks, or oversized pipes that temporarily hold rainwater during a storm and release it slowly over time. For small projects on small lots, providing a detention facility can be extremely challenging and often prohibitive. A suburban detention pond might take up a quarter-acre – clearly impossible on a single infill residential lot of roughly the same size. Even underground vaults or infiltration trenches can take up a lot of space and be expensive to construct.

Some cities provide thresholds or exemptions for small disturbances – for example, no detention is required if the total new impervious area is under 10,000 square feet or if the site is below a certain size. But not all do, and even if detention is not required, stormwater quality treatment might be (e.g., bioswales or filter structures to treat the first flush of runoff). Some cities may also exempt one- and two-family buildings from these requirements, applying them only to projects with three or more units. For a missing middle housing project on a 50-ft. × 150-ft. lot, dedicating any space to stormwater detention can be difficult. The site may not have extra space after fitting the building, parking, and required setbacks.

If a small apartment is replacing one single-family house, neighbors and regulators may be concerned that increased roof and pavement area will worsen drainage or flooding. Opponents of middle-scale housing often cite this – the idea that more impervious cover will overload aging drainage systems. In response, some jurisdictions have actually tightened stormwater rules for these infill projects. That approach addresses environmental impacts, but it can also raise construction costs. If every fourplex needs a complex stormwater system, it makes it more expensive to build.

There are strategies to mitigate this barrier – such as fee-in-lieu programs, off-site stormwater management, or shared facilities – that can help. A city might allow a small developer to pay into a fund for regional stormwater solutions instead of building their own pond. Or, if doing multiple cottages on adjacent lots, a shared stormwater facility in the courtyard could serve all units collectively. Planning departments can coordinate with public works to see if scaled requirements or waivers are possible for projects adding only a minor amount of runoff, especially if the existing infrastructure can handle it. Modern low-impact development practices, such as permeable pavers, rain barrels, and green roofs, can also help meet requirements in a space-efficient way – but again, they add cost and maintenance responsibilities that small landlords might struggle with.

5.2 Impervious Surface Limits and Grading

Some codes directly limit the percentage of a lot that can be covered by impervious surfaces, such as roofs and driveways, with the remainder requiring pervious landscaping. This is often in the zoning code as lot coverage rules or in stormwater codes to ensure infiltration. A duplex might be able to comply easily, but a fourplex with parking might push over the limit, forcing design compromises. For example, if a town requires no more than 60% impervious cover on residential lots, adding more units usually means more roof area and potentially more paved area for walkways or parking. This makes it hard for the project to stay under the cap without constructing expensive permeable pavements or reducing the building footprint, which means fewer units or smaller units.

Additionally, stormwater management plans and calculations add a layer of engineering that small developers may not be familiar with. A single-family home builder might not need to hire a civil engineer for a lot, but a six-unit project might require a full drainage plan signed by an engineer, including grading, drain pipes, and connections to city storm sewers. This increases soft and hard costs. In some cases, hooking into an existing storm sewer for discharge may not be readily available, leading to requirements such as digging up the street to install a new inlet or retention system – a cost that could break a project’s budget.

For planners, a key step is to coordinate with stormwater officials early when encouraging middle-scale infill. Some possible solutions include:

- Establishing tiered requirements where small projects under a certain area of disturbance have simplified stormwater criteria or are exempt from detention, requiring basic best practices like directing downspouts to yards or gardens.

- Ensuring stormwater requirements are not established or tiered based on use but instead based directly on disturbance. Projects that have stormwater impacts should be subject to the same standards regardless of whether they are single-family, multifamily, or commercial. In most cases, this likely means increasing requirements for single-family and lowering requirements for multifamily and commercial.

- Creating a pre-approved toolkit of small-scale stormwater BMPs (Best Management Practices) suitable for infill.

- Allowing consolidated stormwater management for multiple small projects. For example, if a city has a vacant lot or park nearby, fees from scattered small developments could fund a larger basin there that offsets their impact.

- Encouraging permeable paving for driveways and walkways by counting it as pervious surface in coverage calculations, thus giving developers an incentive to use it and meet limits without reducing building size. Many codes already do this to some extent.

In summary, while stormwater regulations are crucial for flood control and water quality, they can become a significant cost center for small projects. Being mindful of scale-appropriate solutions and providing flexibility or mitigation options can ensure that a new fourplex does not need a full-blown subdivision-style stormwater system. A balance can be struck where infill housing contributes to better stormwater outcomes without imposing unrealistic infrastructure on tiny properties.

6. Utility Connection Barriers: Taps, Meters, and Infrastructure

Even if a small multifamily building clears zoning, building, fire, and stormwater hurdles, it still needs basic utilities, such as water, sewer, gas, and electric. It is here, in the realm of public works and utility providers, that another set of hidden barriers can emerge. Utility policies sometimes classify any building larger than a single-family house as “commercial,” resulting in higher fees and more stringent requirements. The cost of connecting a four-unit building to city utilities can thus be far greater than four times the cost of a single-family hookup – a shock to an infill developer’s pro forma.

6.1 Water Service and Backflow Prevention

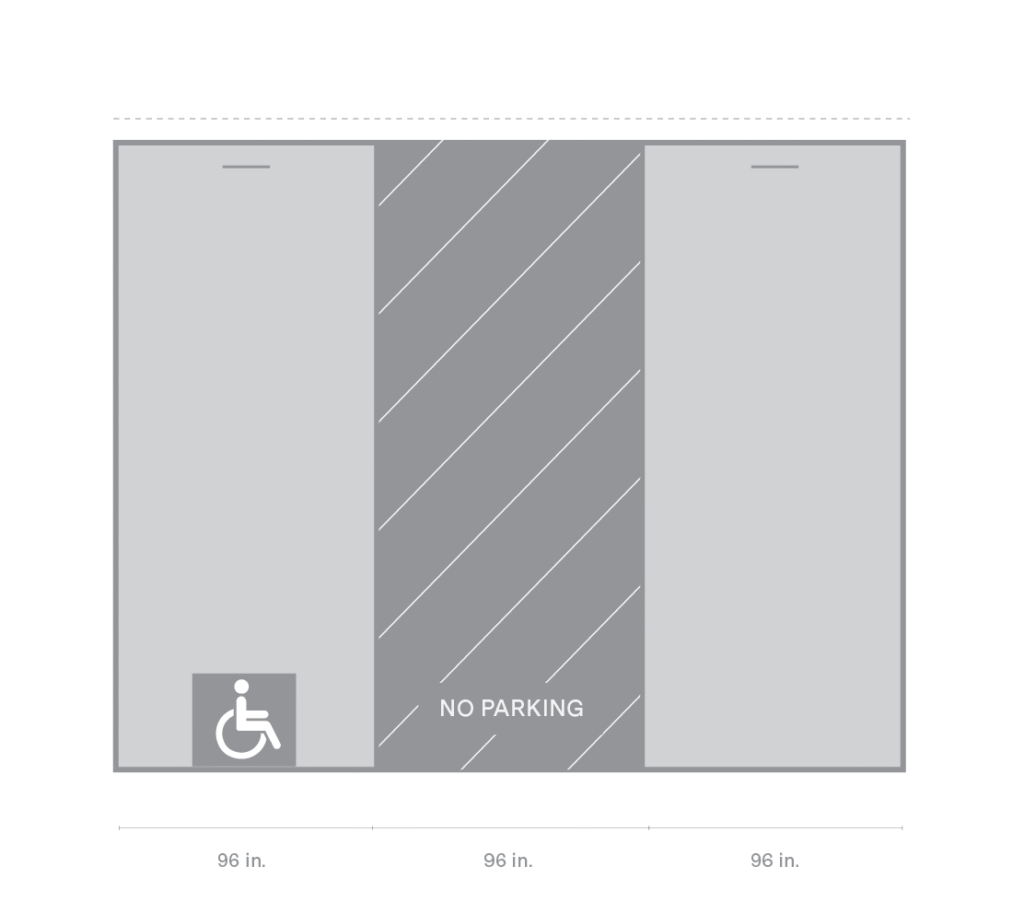

One of the most cited examples of a utility hurdle is the water connection for small multifamily. In many cities, when you build a duplex, you can use either a single residential water meter or two separate residential meters, one for each unit. But if you build a triplex or fourplex, the water utility may require you to treat it as a commercial account. This can mean:

- Larger meter size: A 1.5-in. or 2-in. meter may be required instead of a ¾-in. residential meter due to perceived (but often not realized) higher demand.29 A larger meter has a much higher tap fee (sometimes thousands of dollars more) and higher base monthly charges. For instance, a typical ¾-in. water tap fee might be $1,000, while a 2-in. commercial tap could be considerably more, not counting usage charges. In Memphis, for example, system development charges for a 2-in. meter cost the developer $5,000 per building, while in Portland, Oregon, charges exceed $38,000 for a meter of the same size. Recognizing this barrier to construction, the Portland City Council voted in July 2025 to temporarily exempt new housing from paying system development charges as a means of reaching their stated housing policy goal of 5,000 new units over the next three years.30

- Separate meters for each unit or a master meter: Some utilities require each dwelling unit to have its own meter (to bill separately), which in a fourplex means four meters. That’s four connection fees and four monthly service charges. At other times, utilities will not allow four meters on a small lot and may require a single master meter (for a commercial account) to serve the entire building. Either scenario can significantly raise costs compared to having one house with one meter.

- Backflow prevention devices: As seen in Memphis, the local utility deemed buildings with more than two units as commercial, requiring a backflow preventer on the water service. Backflow preventers are valves that stop water from flowing backward into the public supply, protecting against contamination. While a good safety measure, they are generally required for a water service to a commercial or industrial building or an irrigation system. These devices can be expensive, often require a heated enclosure if they are located outside, and may also reduce water pressure to the point of requiring a booster pump depending on the water pressure provided by the utility and the number of floors.

In effect, a fourplex may face water connection requirements more akin to those of a large apartment or commercial building than a single-family home. Planners working on missing middle initiatives might collaborate with the local water utility to review and adjust policies as needed. For example, raising the threshold for commercial classification from two units to six or eight units would allow small multifamily to be processed like residential hookups. Based on our experience in Memphis with Malone Park Commons, the threshold was increased by the local utility from two to four units due to the local building code amendment removing the sprinkler requirement for three- and four-family buildings. This means a fourplex is now allowed to use a simpler residential meter and is no longer required to have a backflow assembly.

6.2 Utility Connection Fees and Processes

Beyond physical hardware, the fees associated with utilities can be high. Many jurisdictions charge system development fees or impact fees per new dwelling unit for water and sewer. A single-family house might pay one fee; a fourplex could pay four times that or more in some models. If these fees are not calibrated for small projects, they can total tens of thousands of dollars, which for four units might be insurmountable. Some cities have started reducing or waiving these fees for affordable housing or Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) to encourage development. A similar logic could extend to missing middle – for example, charging a fourplex the same total hookup fee as a duplex, recognizing its smaller scale and beneficial infill nature.

Another consideration is electric and gas service. While it is usually simpler, there can be issues if the utility requires space for meters and other equipment. A row of four electrical meters might need an outdoor wall or space that could conflict with the design. Or, if you have a live-work unit, the utility may require separate electrical services for the commercial areas, adding complexity. Generally, these are more minor issues but still require planning. HVAC units also factor in here: more units mean more outdoor AC compressors, which may require additional electrical hookups and physical space.

In summary, hooking up a small multifamily building can involve outsized costs for taps, meters, and lines. These are often invisible to policymakers focusing on land use and zoning. Yet they can make a viable project turn infeasible in an instant. Addressing these issues requires collaboration between planning departments, utility departments, and sometimes state regulators. When done right, reforms can ensure that adding housing units does not mean duplicating commercial-scale infrastructure on every lot. Instead, we can move toward integrated, right-sized utility solutions – for example, clustering meters in one cabinet, using a single line for multiple small units, or waiving certain devices if the risk is low – to support the gentle densification of neighborhoods.

7. Other Local Code Hurdles: Parking, Taxes, Trash, and More

Apart from building, fire, stormwater, and utility codes, a number of other local ordinances and practices can create additional headaches for small multifamily projects. These may not always be “codes” in the strict sense; some are policies or customary requirements enforced during permitting. But all can pose barriers beyond zoning, including parking design rules, property tax classification, waste collection, and the placement of mechanical and HVAC systems.

7.1 Off-Street Parking Design and Site Layout

Parking requirements themselves are typically part of zoning – cities often require a certain number of spaces per unit (or not, as of late). Many places have reduced or eliminated parking minimums for small infill housing, recognizing the need for flexibility. However, even when fewer spaces are required, the design standards for parking lots and driveways can be problematic on small sites. For instance:

- Driveway width and apron requirements: A single-family home might get away with a narrow driveway, but a multi-family building is sometimes required by code to have a wider driveway or two-way drive aisle to access parking. On a small lot, a wide driveway can consume a lot of frontage and yard space. If regulations insist on a wider drive to reach rear parking for a fourplex, that might not fit an infill lot. Allowing narrow driveways or alley access is critical. For example, a ten-foot driveway can adequately serve four to six parking spaces.

- Accessible parking: If a project requires a specific number of spaces, it may need to include an accessible parking spot with extra width and an access aisle to comply with accessibility regulations. The model International Building Code, copying from Americans with Disabilities Act standards, requires one accessible parking space if a total of up to 25 spaces are provided.31 So, even a fourplex with four parking spaces is required to make one of them compliant with accessibility standards, which requires ample space and proper grading. That space, plus the aisle, could take the place of two normal spaces.

- Parking lot landscaping and setbacks: Commercial development often requires landscaped islands, perimeter buffers, lighting, and drainage infrastructure in parking areas. If a small multifamily project is treated under the same standards, a five-space parking lot might be required to have a tree island or a buffer planting strip, etc. This is more typical if the project is reviewed as an apartment complex. Some codes exempt small residential parking areas from those requirements, treating them like residential driveways.

- Loading or turn-around: If local fire or traffic codes require a turnaround for any parking area designed for more than a few cars, a middle-scale housing development might have to pave a hammerhead or circle, which may be wasted space for such a small project.

A more practical solution is to keep parking as informal as possible, using street parking or allowing parking pads off an alley, for example. Many communities today are reducing or eliminating off-street parking minimums for these small projects entirely to avoid these site plan complexities. That may not be feasible in every jurisdiction, so planners should consider how to tailor parking design standards for small multifamily infill developments.

7.2 Property Tax Classification and Assessments

An often overlooked “code” issue – more of a statutory one – is how properties are taxed. In some states, property tax assessment ratios differ between residential and commercial properties. Tennessee is one such state – residential property is assessed at 25% of its appraised value, but commercial property at 40%. Crucially, Tennessee considers any residential building with more than one rental unit as commercial for tax purposes. That means a duplex or fourplex held by a landlord would be taxed at the higher commercial rate, increasing the operating costs. Essentially, a fourplex owner in Memphis could pay 60% higher property taxes than if those same four units were each on separate lots as single-family homes, since four separate houses would each count as residential at 25%. For a small developer trying to offer attainable market-rate rentals, this tax treatment can really pinch finances, forcing higher rents than otherwise needed. In general, this may require state-level advocacy to change definitions or ratios.

Planners can team up with housing policy advocates to push for reforms, such as reclassifying two- to four-unit residential properties as residential for tax purposes. This would align taxes with the reality that a fourplex is housing, not a commercial enterprise on par with a commercial building. If statutory changes are difficult, cities may consider property tax abatement programs or incentives for small multifamily properties. For example, a city could provide a partial tax abatement for ten years on any new fourplex to offset the higher assessment ratio. The key is to identify if your locale has this kind of baked-in disadvantage and then quantify its impact – it might be significant enough to discourage anyone from building small rental housing at all.

7.3 Waste Collection and Service Rules

Trash and recycling might seem mundane, but they can create logistical, space, and cost issues. Many cities have thresholds for municipal garbage collection. For instance, the city will only pick up trash from buildings with up to four units, provided they have individual carts. Anything larger must contract a private dumpster service. Some cities cap it at two units, while others cap it at six or even eight. If a small apartment falls outside the cutoff, the owner has to pay a commercial trash hauler on a regular basis. That may not sound huge, but commercial trash service often means needing a dumpster or large bins and paying monthly fees – a different model than just having a couple of rollout carts for each home.

The presence of a dumpster introduces a design consideration: where to locate it? Many zoning codes require dumpsters to be enclosed by a fence and located to the rear or side, with a concrete pad. Enclosures may also require landscaping or some other type of screening. Dumpsters must also be placed in an accessible location for the hauler. On a small property, squeezing a dumpster enclosure could be very challenging.

If there are only four or six units, perhaps the waste generation is not much more than that of a couple of houses, and using rolling carts could be sufficient. Planners may need to coordinate with sanitation departments to extend residential service to middle-scale housing.

Additionally, recycling and compost requirements may apply – some jurisdictions mandate that apartment buildings have recycling service, which could mean extra bins or dumpsters. Compliance for a small multifamily building can be tricky if space is limited. There might also be rules about how far the bins or dumpster can be from the curb for pickup, which influences site layout.

From a policy standpoint, ensuring that small infill projects are not forced into expensive commercial trash contracts is part of keeping operating costs down. The Public Works department could decide that anything under eight to ten units can opt into city solid waste service rather than defaulting to a private hauling service.

7.4 HVAC and Mechanical Equipment Placement

While not a “code” issue per se, accommodating mechanical systems in a small multifamily can be a design hurdle. Multiple HVAC units have to go somewhere – often on the ground outside or on the roof. Zoning or local ordinances sometimes have rules requiring mechanical equipment to be screened from view or kept out of setbacks. A single house might have one or two air conditioning condensers, but a fourplex could have four, one for each unit, unless a central system is used. Four condensers lined up could encroach into a side yard or rear yard, so the developer may need a variance or to build a screening fence. A simpler solution would be to allow mechanical equipment to encroach into a required side or rear setback. If the solution is to put them on the roof, then structural accommodations are needed, and possibly noise considerations if near windows.

Similarly, the number of utility meters, transformer boxes, gas regulators, and other equipment all increase as unit count grows, and require placement. Especially for small multifamily buildings on infill lots, this may create conflicts with neighboring property lines. Similarly, multiple vent terminations for bathroom or kitchen exhausts may create code issues for small multifamily buildings on smaller lots. A tightly spaced infill project needs to be clever in routing all these vents to either the roof or a wall with sufficient setback. This may add cost in terms of more ductwork or soffits. While these issues are not the typical policy work that planners come to expect, these considerations can be important details to ensure that small multifamily projects can locate necessary mechanical equipment, sometimes with minor encroachments.

7.5 Other Odds and Ends

Every locality will have its own quirks. Some other possible hurdles:

- Subdivision or land division rules: If the intent is to sell units, such as townhomes or condos, then either subdivision or condo mapping is required, which can be complex. This goes beyond building codes, but it is a consideration for planners in enabling small-scale homeownership of multifamily units. Planners should be familiar with laws governing condominiums, horizontal property regimes, and parent and child lots in their states and local jurisdictions. These structures could be valuable tools to unlock opportunities to support middle-scale housing development and new pathways to homeownership.

- Impact fees or school fees per unit: Some areas charge a flat fee per unit to fund schools, parks, and other public services. Five $10,000 fees on a five-unit building is $50,000, whereas a large single-family home might pay one $10k fee – an imbalance that may be worth reviewing if your jurisdiction imposes impact fees. Consider capping fees for small multifamily or scaling them by square footage instead of per unit.

- Construction permitting process: Small multifamily buildings permitted as commercial construction rather than residential may encounter a more rigorous permitting process than a single-family home. More code complexity often leads to more review steps and cycles, especially if plan reviewers are not as familiar with small multifamily projects. Consider offering a pre-approval process to allow small developers to have their stock building plans reviewed before they have a property under contract or financing to close, allowing for a streamlined review once the project is ready to be built.

For planners, the lesson is to take a holistic view of the regulations that affect development. When undertaking an initiative to allow more missing middle housing in your jurisdiction, planners should review building codes, public works standards, fire codes, and even tax codes that could hinder the effort. A coordinated reform package – or at least parallel efforts – can then tackle these alongside zoning changes. In the final section, we will discuss specific action steps that planners and allied officials can take to overcome these hidden barriers and facilitate more middle-scale housing development in their communities.

8. Action Steps for Planners: Clearing the Path for Small Multifamily

Creating pathways for small multifamily housing requires more than just zoning changes. Planners can play a key role in convening different departments, drafting updates to local codes, and advocating for state-level adjustments. Here are some concrete action steps for planners and policy-makers to consider:

- Address Middle-Scale Housing Barriers in the Comprehensive Plan: Many comprehensive plans now specifically address missing middle housing and goals to enable more of it. Land use elements of the plan may address areas where missing middle housing is encouraged, and policies may be recommended to facilitate zoning changes that enable missing middle housing. Don’t stop at zoning. Use the comprehensive plan as an opportunity to investigate all barriers preventing your community from getting more middle-scale housing built, so the comprehensive plan’s goals for missing middle housing can be implemented.

- Find your Malone Park Commons: Some of the best resources for planners to understand middle-scale housing and barriers to delivery are the people working in your community every day to make middle-scale housing work. Middle-scale housing developers can help planners understand costs, pro formas, processes, and challenges encountered across local codes, regulations, and rules.

- Form an Interdepartmental Task Force: Bring together building officials, fire code officials, public works engineers, utility representatives, and other related staff to review how current codes treat small multifamily projects. Identify inconsistencies or excessive requirements. Use real examples (or pro formas) to illustrate how small multifamily projects are handled under each department’s codes, regulations, and rules. If need be, include outside expertise like builders, architects, or engineers to help bring real-world impact into focus. Make the goal clear without asking others to compromise their values. This collaborative review can build understanding and support for right-sizing regulations.

- Develop a Small Multifamily Building Code Amendment: If your state allows local building code amendments, consider adopting an alternative compliance path specifically for small multifamily buildings (e.g., for a fairly low-density city, this might be those with three to twelve units and under three stories; for a higher-density city, this might be single-lot multifamily up to six stories). Key features might include: allowing 2-hour fire separations in lieu of sprinklers for certain unit counts, permitting NFPA 13D or 13R sprinkler systems if used, single-stair design options, narrower corridor allowances, and use of IRC structural prescriptions. By codifying these, cities can give developers predictability and potentially avoid needing state legislation if it falls within their local authority.

- Advocate for State Code Changes if Needed: In some cases, state law may restrict local flexibility. Planners can compile data and case studies to lobby for state code amendments or bills, or even write the bills themselves. North Carolina’s success with HB 488, bringing three- and four-unit dwellings under the residential code, and Tennessee’s HB 2787, allowing sprinkler flexibility for three to four units, can be cited as precedents. Emphasize that these changes can boost housing supply without compromising safety.

- Get Involved with Influencing National Model Codes: Planners can play a role in shaping the building codes, an area where the profession is underrepresented today. National model codes, such as the International Building Code (IBC) and International Residential Code (IRC), are updated through open processes led by the International Code Council (ICC) and other standard-setting bodies. Participating in public comment periods, supporting code change proposals, and collaborating with local building officials to submit recommendations are all ways planners can ensure that middle-scale housing and community development goals are reflected in the next generation of codes. Even planners who cannot formally vote can lend expertise and advocacy that helps balance life safety with broader policy objectives.

- Calibrate Development Fees and Taxes: Review impact fees, utility connection fees, and tax assessments for any inequities affecting small multifamily properties. For example, consider fee reductions for the first few units in a project. If you cannot work with your finance department or state legislature to classify small multifamily buildings as residential property for tax purposes, consider a rebate or abatement program instead that could encourage developers to build middle-scale housing.

- Update Local Fire Codes and Policies: Coordinate with the fire department to adjust requirements, such as alarm systems and fire access, for small projects. For instance, raise the threshold for requiring a full fire alarm panel – maybe only mandate it if a building has more than eight units or more than two stories. Develop guidelines for single-stair buildings up to a certain height to provide more flexibility with egress requirements.

- Work with Utilities on “Small Infill” Standards: Engage water and sewer utilities to create a separate category for small multifamily developments. This might involve:

- Allowing the use of standard residential service lines and meters for up to four units without requiring costly upgrades.

- Eliminating the automatic requirement for backflow preventer assemblies on small residential or multifamily properties, or providing them at utility expense if truly needed, since they protect the public system.

- Structuring billing so that these buildings can have either individual unit meters or master meters with equitable charges, rather than defaulting to the most expensive option.

- Involving utility representatives to review and approve differentiated costs or connection policies so that small multifamily buildings pay a reasonable, proportional fee and can connect using the same requirements as single-family homes.